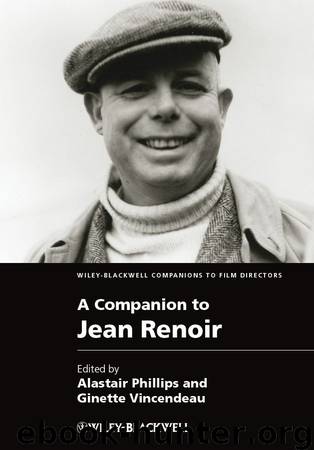

A Companion to Jean Renoir by Alastair Phillips & Ginette Vincendeau

Author:Alastair Phillips & Ginette Vincendeau

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: John Wiley & Sons

Published: 2013-03-27T16:00:00+00:00

Writing in Bazin

“The equal of novelists.” With this boast Bazin broadcasts the arrival of cinema at the doorstep of postwar modernism. It took La Règle du jeu, Citizen Kane (Orson Welles, 1941), and Paisà/Paisan (Roberto Rossellini, 1946) to prove this medium mature enough to confront the world as an adult. Although each of those three modernist masterworks came from an original script (and, incidentally, each embeds a moment of staged theater), Bazin associated them with the novel. The flexibility of the novel, far younger than painting and theater, gives it advantages that cinema shares. In novels and films the reader or spectator is transported into a world through the interweaving of description and narration, where action leads to reflection. In most novels, characters, plots, and themes emerge from an abundance of details that signal a much wider reality than what is being represented; cinema goes further in this direction, with excess information automatically packed onto its image and sound tracks. This constitutes the primary “realism” linking these two art forms in Bazin’s mind, lifting them above theater and painting in their pertinence for postwar culture.

As for Renoir, he made the same aesthetic preference for these two media known in 1969: “I like books and films that give the impression of a frame too narrow for the content” (Braudy 1972: 65). Perhaps this is why that same year he acknowledged the kinship he felt with creative writers when he proudly dubbed his new company “La Nouvelle Édition française.” Its first production would be his masterpiece of unframeable realism, La Règle du jeu. The epigraph to the screenplay of that film published in L’Avant-scène cinema is taken directly from Renoir’s bold advertisement: “The first generation of the cinema belonged to producers; the second, to directors; now the third has appeared, and it belongs to authors” (Esnault 1965: 7). Philippe Esnault’s preface elaborates: La Règle du jeu “reveals a spatio-temporal conception that suggests a transition in film language from that of dramatic construction to cinematic writing [l’écriture cinématographique]” (Esnault 1965: 13). While Renoir would write and direct plays in the 1950s, Esnault, following Bazin, believed that Renoir possessed the sensibility of a novelist; and indeed when the great auteur was no longer able to make films, he published three novels.

The phrase “cinematic writing” brings Robert Bresson on stage, that arch-enemy of theater. Bresson and Renoir were so very different (representing France’s “lean and fat traditions” respectively, Roger Leenhardt (1946: 110) had said), yet both were adept in wielding the caméra-stylo, that powerful implement Alexandre Astruc had identified as belonging to a new avant-garde capable of “cinematic writing” (2009: 32). Where the 1920s avant-garde had labored over intricate image design and complex narrative syntax, their films were often opaque. By contrast, the postwar avant-garde heralded by Astruc and Bazin conducted their sallies or experiments at another level, that of character, theme, and plot. In this, they followed Jean-Paul Sartre’s contemporaneous attack on surrealism, indeed on poetry altogether, when he urged writers to respond to their situations with transparent and direct prose (Sartre 1988: 151–164, 339–345).

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(5186)

Gerald's Game by Stephen King(4659)

Dialogue by Robert McKee(4407)

The Perils of Being Moderately Famous by Soha Ali Khan(4225)

The 101 Dalmatians by Dodie Smith(3515)

Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting by Robert McKee(3471)

The Pixar Touch by David A. Price(3443)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(3313)

How Music Works by David Byrne(3273)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(3077)

Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald by J. K. Rowling(3061)

Slugfest by Reed Tucker(3008)

The Mental Game of Writing: How to Overcome Obstacles, Stay Creative and Productive, and Free Your Mind for Success by James Scott Bell(2910)

4 - Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire by J.K. Rowling(2705)

Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting by Syd Field(2649)

The Complete H. P. Lovecraft Reader by H.P. Lovecraft(2567)

Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Sex, Deviance, and Drama from the Golden Age of American Cinema by Anne Helen Petersen(2527)

Wildflower by Drew Barrymore(2490)

Robin by Dave Itzkoff(2443)